How Learning to Embrace Diversity Can Change the Trajectory of Your Life

A local cross-country ski race set me on the path to finding my authentic self

My teachers labeled me as a non-conformist. They hissed the accusation with disapproval that bordered on contempt.

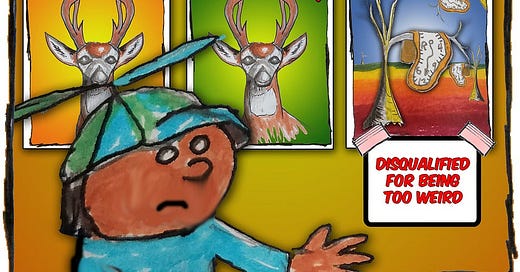

In art class, all the other kids did portraits of white-tailed deer looking out from the canvas. We had the illusion of choice but there was an unspoken pressure to pick an “appropriate” subject.

During the art show, the halls displayed portrait after portrait of white-tailed deer. “Look at that one, he’s a big six-pointer. Oh, there’s another with a magnificent irregular rack.”

Inevitably, the chatter would dry up when the parents came upon my contribution. I always provided some Salvador Dali inspired tormented landscape in bright and vibrant colors.

“I was going to do a deer,” I explained. “But the other kids used up all the brown paint.”

The parents would nod and say, “That’s different.” Then they’d take the art teacher and the principal and the superintendent aside. They’d stand in a corner muttering words like “deviant” and “bad influence” and “not around my kids.”

Perhaps the worst part was how the “best” artwork would be selected for display at local businesses and restaurants. My family would go out to eat and there would be the masterpiece of one of the classmates who did nothing but scowl at me throughout art class. Another dinner ruined by the mangled representation of a deer. My work was never chosen for display.

Conformity provided the backbone of my home town’s ideology. “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” they said, deliberately ignoring all the things that were broken. Fortunately, I would grow to discover that diversity can only be suppressed, never eradicated.

The ski race

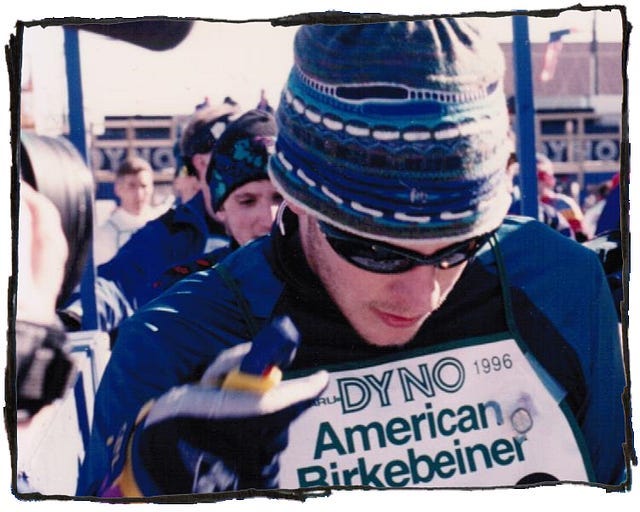

I had the good fortune of growing up thirty minutes away from America’s largest cross-country ski race. It’s called the American Birkebeiner, and it’s a grueling 50 kilometer slog through difficult terrain in the dead of winter.

My grandparents’ house happened to be right on the race course, so it was impossible for my family to ignore this event. The final stretch of the race crossed a frozen lake, so we could sit in my grandparents’ kitchen and watch the line of skiers stretching out into the distant hills.

It seemed endless.

Everybody in my town did their best to ignore the ski race. Tradition stated that the only appropriate activities in Northern Wisconsin needed to involve either a motor or a gun. The term “silent sports” to them was an insult. In fact, they considered it a disrespectful affront to their way of life.

There’s a lot of bubbling hostility beneath the surface of a small town.

Tension between the skiers and the locals

Over the years, the American Birkebeiner has grown to over 13,000 participants. It’s the Boston marathon of cross-country skiing. It brings in tens of millions of dollars to the area.

Yet, the small town locals can barely keep themselves from spitting when they talk about it. “When that dang Birk-EE-binder is going on, it’s impossible to drive through town,” they say.

As the popularity of the Birkie grew, ski trails began to pop up all over the state. The locals considered this an encroachment on their traditional forms of recreation. Grooming and setting ski tracks is an involved and delicate process. All it takes is one joker with a snowmobile to destroy an immaculate trail, and that happened often.

Skiers quickly learned they weren’t allowed to complain. The culprits were turned into cult heroes in the local watering hole.

“I call cross-country skiers ‘click-clicks,’ because that’s the sound they make when you run them over with a snowmobile. They’re nothing but a bunch of arrogant, entitled, rich jerks from the Twin Cities.”

I didn’t think of them that way. I thought they were magical.

A parade of inclusion

Naturally, I was instantly drawn to the Birkie. That must have been the non-conformist taking the controls.

I never liked sports when I was in high school. All the sports took place in a loud and smelly gymnasium. We had to go and watch basketball games where the same five guys ran back and forth, back and forth, over and over.

The team did tryouts because not everybody was allowed to participate. Only the “best.” The same as how only the “best” artists got their work put on display.

Somehow all the best athletes were always the kids of prominent people in the town. When the team didn’t win, we were told it was because those of us in the crowd didn’t show enough support. I mentioned this to my mom and she said that when she was growing up, the girls weren’t allowed to play at all.

She found inclusion in the ski race too:

When I watched the American Birkebeiner, I saw something completely different than anything I’d ever seen. This was an event that welcomed everybody. Not just men and women, but skiers from other countries! People who spoke different languages were welcomed and celebrated. People who believed different things were also encouraged to attend. I was astounded by the achievements of blind skiers who did the event with a guide, and adaptive athletes who managed to participate after losing one or more limbs.

Absolutely everyone was welcome.

Absolutely everyone was celebrated.

There were no rigid, unspoken expectations that required your compliance.

I’d never seen that before.

I also appreciated that it wasn’t the same group going back and forth in an endless loop without any progress. Everybody was given their opportunity to shine. They came flashing by on their way to the finish line and then they were done. Then came the next group and the next. Everybody was given a chance. Everyone had their moment to shine.

I didn’t realize it, but I was hooked.

From college drop-out to dump truck driver

I’d intended to go to college and “show everybody.” Instead, I washed out in a couple weeks. I was astounded to discover that even though I thought I had rebelled against the conditioning of my upbringing, it had nevertheless branded me.

I’d been imbued with an inherent sense of disrespect for the city and all things in it. I was intolerant of different cultures. My humor was simplistic and abrasive. I went to the city because I thought that was where I belonged, and I discovered that I didn’t fit there either.

I took a hard look in the mirror and was dismayed by the truth. I felt as low as I can remember.

That experience humbled me. I went back home and worked as a dump truck driver. My dump truck leaked steering fluid. My clothing was stained with oil and dirt. I felt discarded and unwanted. I needed something that made me feel included.

So, in the time of uncertainty, I signed up to ski the Birkie.

At war with myself

The men I worked with were loud in their opposition to all things related to cross-country skiing. “Those dang skiers are in town with their Spandex clothing. What makes a grown man go out in public in Spandex? It’s shameful.”

This they said at lunch as they grasped on to peanut butter sandwiches. They left gray/black streaks on the bread because they never bothered to wash their hands. “We don’t want those entitled skiers here. They don’t belong here. This is our land!”

I hoped they wouldn’t notice the second-hand pair of cross-country skis tucked away in the back of my car. I brought them so I could go skiing after work.

The first year I skied the Birkie, I wore a regular pair of pants and a wool shirt. I couldn’t bring myself to dress like a “hoity-toity” skier, and I laughed at people who did.

I told myself, “This is the way people have dressed for a hundred years. We live here! We know better! Why did skiers think a fancy pair of stretch pants could give them an advantage? This was the way it had always been done.” It never occurred to me that I was regurgitating the philosophy of rural art teachers who insisted you shouldn’t paint anything but the portrait of a white-tailed deer.

I skied a full year before I realized my own hypocrisy. When I finally did, I was more terrified than embarrassed. How had they managed to get me to repeat those arguments? What other awful things did I reflexively repeat without even thinking about it?

In that moment, I began my true path to self-discovery. I realized that as an adult, you have to reexamine everything you believe to be true. This is especially important if you were exposed to toxic communities.

By year three, I had come a long way.

By the way, it’s not Spandex, it’s Lycra.

A rainbow of of color and diversity

The American Birkebeiner was a splash of color and happiness in an otherwise drab and intolerant world. I met people from exotic places who spoke different languages. They invited me to come and ski the famous race in their country. So, I saved up my money and I went.

Here I am skiing in Australia (I’m lapping the guy in blue):

The Birkie is a parade of joy. Competitors and spectators shower you with encouragement every centimeter of the way. I realized that is a wonderful metaphor for life.

Life is not a basketball game played within an artificial set of boundaries designed to make stars out of a handful of competitors while everyone else is forced to watch.

No, life is a point to point race. We all deserve our opportunity to compete. We all deserve to have a moment where our courage is recognized. We all deserve encouragement and inclusion.

I realized where I needed to be

During my year of uncertainty, I began to chip away at all the misguided things I didn’t even know I believed.

Monday after the race, I went back to work. The same group of guys were sitting around eating their dingy sandwiches on overturned 5-gallon buckets. “What did you do last weekend?” somebody asked.

“I skied the Birkie,” I said.

A silence descended over the room. Slowly, everyone turned to look at me. I dug into my pocket and withdrew my finisher’s medal. “This is what they give you. I know it doesn’t seem like much reward for skiing 50 kilometers.”

One of the men reached out. I handed him the medal, not sure if he was going to break it or throw it away. Instead, he took a close look at it before passing it on. The medal made its way around the room. I was surprised to see that they all handled it with something close to reverence.

The foreman was the last to look, and when he handed it to me he said, “Well, you’ve done something that nobody I know has ever done.” There was respect in his voice and maybe, just maybe, a little bit of envy.

At the end of the year I quit that job and I went back to college. Like a spectator shouting encouragement during a marathon, the Birkebeiner gave me the impulse I needed to change the trajectory of my life.

I guess my teachers were right. I was a non-conformist. I still am. The difference is that today, I know that there is a place in the world for everyone.

“I'd rather Be Writing” exists because of your generous support. If you have the means please consider upgrading to a paid sponsorship. I have payment tiers starting at as little as twenty dollars a year. I'm so happy you're here, and I'm looking forward to sharing more thoughts with you tomorrow.

My CoSchedule referral link

Here’s my referral link to my preferred headline analyzer tool. If you sign up through this, it’s another way to support this newsletter (thank you).

Great story, Walter.

It's amazing how similar our lives were through the formative years and up into college.

I grew up on an island of 4000 people off the Northwest Coast of Canada. Most of the small towns up there were logging and fishing communities. My parents were hippies - they were the ones standing with the Indigenous folks in front of the logging trucks driven by the fathers of my classmates. I was a square peg looking at a board full of circular holes.

Out of high school, I went straight to college in the "big smoke" (what we called big cities like Toronto) and I just couldn't get my footing. I didn't fit there either. There were no open spaces - no forests, no trees, no autonomy. I lasted a year but only because I didn't have enough money to buy a plane ticket home. I worked in a car wash after classes to make enough money to get that ticket.

Once back home, I found a job in a sawmill with a bunch of guys who during lunch would sit on the stacks of lumber and bitch about things. They'd never been anywhere but there, and they were too afraid to change this. The epiphany I had was that I realized that I wasn't. I had only experienced two ways of being that seemed diametrically opposed - yet I could see they were amazingly similar. Both required a high sense of conformity of thinking - of which I do not have a shred of.

After a year, with money saved and a better sense of who I was and where I wanted to be, I went back to college closer to home, in a smaller town (of about 70,000) which was a much better fit. It was easy enough here to find a sense of community. I found an eclectic yet driven crowd through a local running and triathlon club - and I never looked back. Endurance sport changed my life - it gave me calm, purpose, and most importantly self-discipline (an important trait that was missing from my hippie upbringing). In my pre-family days I was disciplined enough in my training to qualify and race at Ironman Hawaii :-)

Being raised in a wilderness environment devoid of structure means I just don't fit in square spaces. These days with my family I have smaller goals but I still keep the discipline of running 6 days a week. With running, I can easily find peace, calm, and autonomy on all of the trails and paths around my home.

IMAGINE … if at the Super Bowl … all the black players took a knee during the national anthem …