How ‘Stranger Things’ Exploits the Generational Trauma of ‘80s Kids

I’ve seen too much tragedy to be entertained by shows that depict threats against children

I grew up in a conservative rural town in the 1980s. My friends lived ten miles away, and we’d ride out to meet each other on dirt bikes equipped with headlamps for the return trip. We’d leave in the morning, and come back at night. Our parents didn’t know where we were.

Today, people lament the loss of freedom and the sense of innocence from those days. How easily they forget that every now and then, a child went missing.

A few nights ago, my wife and I decided to give Stranger Things a try. It’s typical for us to wait 5 or 10 years to watch a fad show. If people are still talking about it, then we figure it must be worth our time.

Lately, I’ve been finding David Harbour compelling. Even when he’s in a fluff project like Gran Turismo, he brings an intensity that’s hard to ignore. He’s a physically intimidating man with a rugged face, but it’s something of a surprise that he’s equally believable when he shows compassion and vulnerability. Interestingly, he’s carving out a career as a hero because his physical appearance lends itself to playing the villain.

My wife and I hit play on the first episode of Stranger Things, and as a child of the ’80s, I admit that the show knew exactly what buttons to push. Even the title credits feel like an authentic relic from that age. They have the flickering jerkiness of VHS.

My wife grew up in Peru, so her experience growing up was vastly different than mine. I realized I had the opportunity to share something about myself. “That’s exactly what we did,” I said. “We played Dungeons and Dragons. We rode around on our bicycles, and we lived under the constant terror that one of our friends would disappear, and nobody would ever find out what happened.”

That’s the truth about the ’80s. I’m not exactly comfortable watching that trauma be exploited for a television show. As close as the show comes to hitting the mark, I think it misses the bigger picture.

Too many kids have gone missing in my lifetime

I don’t know if my memories of the ’80s are unique or if everyone from my generation had the same experience. I remember my mom being worried that we’d be abducted. She’d give us stern warnings, but we were wild and the moment we were out of sight we did as we pleased.

Perhaps every culture has terrifying stories about children going missing. There are legends about goblins or gnomes stealing babies from cribs. We rely on supernatural explanations because we don’t want to face the true horrors hidden within human nature.

I grew up a few hours away from the town where Jacob Wetterling was taken in 1989. That changed things. The vague warnings and nightmares became terribly real. As we rode our bikes at dusk down winding country roads, we wondered if we’d be next.

We pedaled faster.

Stranger Things, too, deals with the theme of a child’s disappearance. As I watched the first episode, it occurred to me the extent to which getting abducted was wrapped up into the fabric of our existence. You can’t have a show about the ’80s without mentioning lost children. I remember the faces on milk cartons. That type of tragedy is as representative of that era as video games, Michael Jackson, and Star Wars.

For me, this was a startling thing to realize.

My complex feelings about ’80s nostalgia

We all wore dingy white shoes with three blue vertical lines. We had windbreakers with rainbow stripes running down the arms. We had dirt bikes with headlamps that allowed us to navigate at night. All that is authentic.

I think it’s important not to confuse your nostalgia for being young with affection for the era when you grew up. I’m grateful to breathe and move and feel the rush of my spirit within my body. Relics from the ’80s remind me of my youth and help me recall long-dormant memories.

The memories of youth are good, the relics of the ’80s often are not.

Arcades were like kid traps

We didn’t have the internet. We barely had computers. Instead, we were captivated by video games. They were simplistic creations with unresponsive controls and terrible graphics, but they were the first step into a world in which anything seemed possible.

I remember begging for a quarter so I could play Asteroids. I recently showed that to my daughters on an emulator console and they simply didn’t understand it. “How could you play this?” they asked. Having seen the advancements since Asteroids, the game itself no longer had any power. It has power over me, but that’s because I remember the smell of the pizzeria where the arcade unit was located. I remember the faces of my friends. I remember their curly hair sticking out from under baseball caps as they awaited their turn.

I remember being honestly fearful they’d be abducted. A stranger offering you a quarter so you could play a video game could easily win your trust.

A need to protect children

A few years ago, I was a member of a search party that found a child that had been missing. My own girls were one year older and one year younger than the victim. They went to the same school. A few days after that, Uvalde happened. I had nightmares for a year in which I was tormented about the different ways my kids might be taken from me.

These things keep happening and our society refuses to do anything about it.

In 1996, a girl disappeared from the town where I grew up. A friend of mine was living there at the time and he said that the local police never even mentioned it. Years later, they claimed to have conducted a comprehensive search, but he insists this never happened.

“I was there!” he said. “I only heard about this case when I saw a special about it ten years later on national news. The local police didn’t do anything! There was no organized, community search!”

When I was a wild preteen pedaling around on my dirt bike, the first thing we learned was to flee the local deputies. We had an instinctive understanding that their investigative techniques amounted to little more than finding a believable scapegoat to blame for the crimes they were tasked with solving.

The tradition of policing in the United States wasn’t born out of a pursuit of justice. They began as slave patrols, and today they still employ remnants of a tradition that is as unscientific and oppressive as white supremacy.

The anti-science philosophy of rural areas

Conservative rural areas reject the concept of scientific study. The same science that leads to the creation of life-saving vaccines is also responsible for the complex forensic techniques that can help find missing children.

Rural areas would rather go to war than take a shot that will stop a deadly virus from killing millions.

After the search party made its discovery, I sat down with the bewildered detective in charge of the case. It was obvious that he was out of his league, and he looked terrified. At that moment, I regretted my failure to make an involved study of the field of forensic science so that I might be of use.

I remember sitting in a science class with the kid who would go on to be the sheriff in my hometown. He disregarded the content and was disruptive to the point where he deprived the other kids of their opportunity to learn.

“We don’t need liberal elites telling us what to do!” is a commonly repeated mantra. Our society doesn’t even offer a counter-argument. The idea of “tradition” is applauded and undeservedly revered. Progress is regarded as an unacceptable risk.

But when something happens to a child in your community, that self-righteous, rebellious attitude has absolutely no solutions to offer. In the case of my town, the local police force immediately called in the city experts who used advanced scientific techniques to find the perpetrator.

Naturally, the media stopped short of thanking the members of the scientific, “liberal-elite” that returned to us the ability to sleep soundly at night. Instead, we were stuck with the Hallmark movie mythology in which the “traditional conservative simpleton” is the one who rises to the occasion.

He doesn’t. All we get from them is book bans, the anti-vaxxer movement, and threats of civil war.

The myth of the dutiful, small-town police officer

In Stranger Things, David Harbour plays a small-town sheriff who takes it upon himself to rescue the missing child. To me, that’s the one element of the show that feels like a complete fantasy.

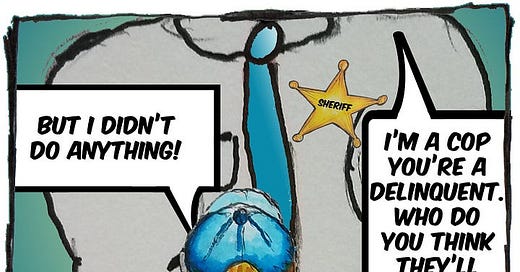

In the ’80s, the supernatural monsters haunted our nightmares, but the local police haunted our waking hours.

“I’m a police officer and you’re a delinquent. If it comes down to your word against mine, who do you think they’re going to believe?”

I’ve been around an unacceptable number of child abductions in my 50 years. American society has grown appallingly numb to how often these things happen, and we never hold the backwards ideology that allows this kind of tragedy accountable. It’s time we dropped the irresponsible fantasy of idealizing rural areas and gave equal time to demonstrate how anti-scientific attitudes result in preventable abuses committed against children.

David Harbour’s character in Stranger Things does not exist in real life. Uneducated, disrespectful womanizers who perch on bar stools and spend their time making rude comments do not “rise to the occasion” to protect children.

This type of person isn’t a “rough around the edges” savior with a heart of gold. More often, this type of person is the monster who exploits innocence and vulnerability at every opportunity.

Perhaps we invent stories about supernatural creatures stealing children away because it’s too painful to face reality. Well, it’s time to grow up and be responsible adults.

I‘m not sure I’ll continue to watch

My wife and I are about four episodes in. So much of the series rings true that it’s unnerving for me, but the hero cop character might make it impossible for me to keep watching.

I might have believed it if they’d made a hero out of the science teacher. I might have believed it if they had chosen a community outcast who spent all his time in the library and was thus regarded with suspicion by the townsfolk.

The hero should have been a Black woman to emphasize how America’s tolerance of misogyny and racist traditions renders our society ill-equipped to offer aid to vulnerable populations. A modern hero must confront both the criminals who commit heinous acts and the social misconceptions that enable the same injustices to repeat in perpetuity.

That’s the kind of social criticism the American population needs to see.

Instead, we got yet another reminder that salvation lies in bowing down before the altar of ignorant authority.

It could be that I’m just too old for this kind of thing. I’ve seen too many tragedies. I know where the real dangers lie. So many of the narratives that infiltrate pop culture are nothing but distractions. The truth is, we know how to protect our kids. We know who the predators are.

And yet, we do nothing.

My CoSchedule referral link

Here’s my referral link to my preferred headline analyzer tool. If you sign up through this, it’s another way to support this newsletter (thank you).

“And yet we do nothing”. So true. It is why we need a new generation of leadership, not the same old same old.

Another con of the weird right is that all crime is in 'the big cities' <cue the horror>. Here in PA, they just had a huge meth lab bust in the center of the state. No big city. No liberal elites ignoring the problem. Just rural folks ignoring what they want to ignore.

As for disappearing children, we have our own fantasies about them. We teach 'stranger danger' when most (more than 70%) abuse against children is by someone who knows the child. Coach, religious person, uncle, etc. And as they age, there is human trafficing. And it is everywhere, urban and rural.

Sometimes all one can do is cry.