Once You’re Down in a Rural Town You’re Never Getting Back Up

What remedial math class taught me about my self worth

My first experiment in rebellion happened in third grade. It didn’t turn out well for me. In fact, the consequences were so painful that, even today, I can’t reflect on it without flinching.

I learned early that rural school served no purpose other than torture. The bus ride took forty minutes, which meant forty minutes of beatings from the older kids, both on the way to school and on the way home. You couldn’t fight back because punishment was reserved for those who retaliated.

“Well, he hit me first.”

“Did you like it?”

“No.”

“Then why do you think it’s an appropriate solution to hit him back? Aren’t you only behaving like him?”

“So, what should I do instead?”

“You should come to me and I’ll tell him to stop.”

“You’ve told him to stop a whole bunch of times and he keeps doing it. Could you try something else please?”

“You’re a very obstinate and disrespectful little boy. If you keep smarting off to me, I’m going to slap you.”

“Wait a minute, so now hitting somebody is an appropriate solution?”

Even today there are 19 states that allow corporal punishment. Why not cut out the middle man and let kids handle it themselves? It’s barbaric. Having been through that experience, I wonder how many districts reserve the beatings for kids who were just trying to defend themselves?

Ask yourself, what’s the real purpose in this kind of punishment?

Physical beatings break you down mentally, but they’re not as bad as the emotional attacks.

Injustice is tough to deal with.

Some part of you knows the whole system is unfair, and you’re inclined to respond. But you’re also conditioned to understand any retaliation on your part will be both futile and painful.

I learned that much.

I knew I couldn’t raise my arms in self-defense. I couldn’t take any action that could be seen. I couldn’t speak defiant words that could be heard. The only thing left was to think insubordinate thoughts.

It was so bad I actually had an inner-dialogue where I debated whether or not they could read my mind.

“I don’t have to believe them. In secret, I don’t. There’s no way they can tell what I’m thinking. They pretend they can, but there’s no way. As long as I keep my expression blank they won’t know… I better not even look at them. They can’t know what I’m thinking, they can’t.”

But I gave myself away in third grade when I deliberately failed a math placement test.

I didn’t think they could make me pay for that. I was wrong.

That morning, I was angry. Perhaps the beating on the bus had been particularly severe. I also had a teacher who despised how I held my pencil. She forced me to get a rubber attachment in the shape of a triangle that would fit over the end.

“There! Now you’re meant to brace your finger against every side of the triangle as is proper. This will prevent you from clutching the tip in your grimy little fist!”

Of course, all the other kids noticed she’d forced me to use this writing attachment. That made me different, and different meant you were a target for even more beatings. They caught my eye and laughed, and I couldn’t take the attachment off for fear of being punished.

To this day, my handwriting is defiantly illegible. I can’t even read it myself. Take that Ms. Second Grade Authoritarian Monster! Out of pure spite, I developed a stunning memory so I don’t even need to take notes. That teacher deserves no credit. My achievements are mine and mine alone.

So, anyway, I was angry. I was holding my dumb pencil and nursing a goose egg and the teacher came stomping around the room with a big stack of math tests.

Math tests!

When did it ever end?

So, I ground up my face into a passive expression because I didn’t want to reveal my thoughts. I’d been a good student the previous year. I’d done all their ridiculous tasks. I’d scribbled accurate answers with my “grimy little fist.”

What good had it done me? Here I was forced to navigate yet another obstacle in an endless row of obstacles. How about trying something different?

The rules of survival I had worked out said I couldn’t do anything they could see.

Well, nobody was supposed to be watching me as I took a test.

The rules said I couldn’t say anything they might hear.

Well, tests were taken in silence.

Ah-ha! It seemed like a perfect plan! I resolved to deliberately get every answer wrong on the test. Fine! Let’s see what happens. Let’s call their bluff.

I remember writing absurd responses. It was the most fun I’d ever had taking a test in my whole life.

What is 8+7?

Answer: 58,641.

What is 50+1?

Answer: 0.

I felt almost good when I handed that test in. There was a little flash of panic as Ms. Authoritarian Monster took a glance at it, but she couldn’t be bothered to read my answers. I’d gotten away with it!

Or so I thought…

I sat down and smirked, even though some part in the back of my mind wouldn’t stop whispering about how this might have been a terrible idea.

A couple weeks later, I’d almost forgotten about the placement test when a gritty announcement came over the PA system.

“Based on your mathematics placement results, here is the list of students that must report to remedial math.”

My hands clenched because I knew. They had me. I knew. Of course they thought it was a great idea to blast the names of all the students who needed extra work at top volume throughout the entire school. Of course they had to do that! It would have been inconceivable to handle a potentially embarrassing moment with discretion.

They never passed up an opportunity to humiliate!

“Remedial, remedial, remedial” was chanted like “shame, shame, shame.”

So I prepared myself and waited, and there it came. My name was announced with all the others.

A couple classmates gave me perplexed looks because they knew I’d been a top math student the previous year. I couldn’t even meet their eyes. I just gathered up my things and got in line with the other kids on their way to remedial math.

Those poor other kids, they were used to being treated like this. They shuffled to stand in line at the door and didn’t look up. I mimicked them.

They already knew where to go, so I followed. We headed down the stairs, past the front door, and into the basement. The remedial math room was also the boiler room. Tubes and ducts covered in asbestos wrap spread across the ceiling like the roots of a vast, subterranean tree.

It was hot in there.

The special education teacher was a gigantic woman who sat at a tiny little desk. She was sweating.

The other kids knew what to do. They took their seats. I waited until last and then settled into an unoccupied desk.

Too little, too late, I was being respectful. I trembled with fear.

On the journey to the room, I’d already conceived of a plan. I now regretted my choice to fail that test. I hadn’t expected to be expelled to this distant penal colony. I had to get out of remedial math.

But I also resolved that this was my problem. I’d gotten myself into this, so it was up to me to get myself out. “Okay then,” I thought, “I’ll ace every assignment they give me. I’ll become a math prodigy. I’ll prove to them through my achievements that I don’t belong in remedial math.”

I even thought that maybe it would be useful to spend the extra time in remedial math. Maybe it could actually help me?

Yeah, I’d learn something, but not that.

The bell rang indicating that the session had begun. I expected the special education teacher to greet us, or to even look up at us, but she did nothing. There was not even a “Hello.” Instead, she gestured at a stack of papers. The kids knew what to do. One of them grabbed the stack and began passing them out.

A worksheet? This was remedial math? You were sentenced to go down to the boiler room and complete a worksheet?

“Fine, I’ll ace this,” I thought. “I’ll… what the heck is this?”

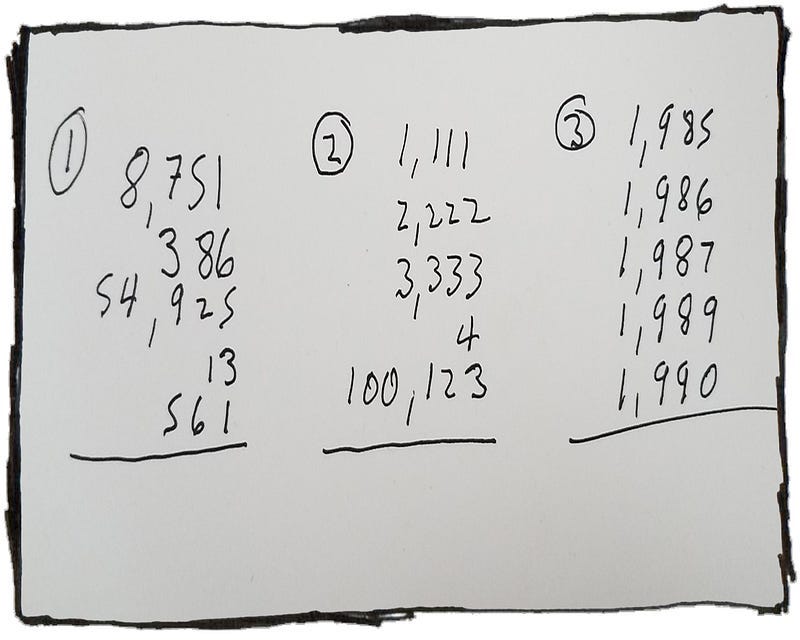

The worksheet didn’t appear to come from any textbook. Instead, it was a copy of something somebody had written up by hand:

In my arrogance, I’d been sitting there presuming that remedial math was going to be cake. The special education teacher had some sort of a degree didn’t she? Wasn’t it her job to make us better at math? Wasn’t it likely that she’d be able to perceive, in short order, that I didn’t belong here?

Welcome to the reality of incompetent professionals, kid.

I looked at the list of problems we were supposed to do and my hopes were dashed. There was no indication of what operation we were to perform.

I didn’t want to, but I raised my hand. Asking questions in the first minute of my first task was not the way to prove I was a math genius, but what choice did I have?

The special education teacher had begun to read a trashy dime store novel. She didn’t look up.

I cleared my throat.

That got her attention. Her eyes narrowed in anger. “What?”

“What are we supposed to do here?”

“Do the problems!” she snapped, smirking at the other kids like the question was funny.

“But it’s just a list of numbers, do we add, multiply…”

A couple of the kids whirled to look at me with pained expressions.

The special education teacher smirked. “Because you asked, you can multiply!” She hissed the final word with vicious delight.

That was like a gut punch because I realized I had no idea how to multiply a big list of numbers like that. I was off to the worst possible start.

If the other students resented me, they didn’t show it. They must have already been beaten down to the point where they knew objections only brought further punishments. They just sighed and got to work. I did too.

I decided to break the long list of numbers into groups of two. So, on a piece of scratch paper, I started multiplying 8,751 X 386. I figured once I got a solution, I’d multiply that by 54,925.

I’d just started making progress when the special education teacher got out of her desk and lumbered around to look at what we were doing. She glanced over the shoulders of a few students and nodded in approval. When she came to mine, her face contorted into an expression of fury.

“What are you doing?”

“I’m multiplying this list of numbers.”

“You’re not multiplying all of them, you’re only multiplying some of them! Why are you leaving out all these other numbers?”

I started to panic. I tried to explain but she cut me off.

“Who told you that you could break the list of numbers up into small groups?”

I was completely unprepared to be under this level of scrutiny. I’d resolved to be diligent and put aside my rebellious ways. Normally if you were hard at work in a classroom, the teacher wouldn’t lay into you even if you were doing it wrong. This teacher was so mad I thought she was going to explode. I felt close to tears.

She grabbed my paper off my desk, crumpled it into a wad and threw it on the floor. Then she grabbed me another. “Start again, and this time do it right!”

I was trembling. I had absolutely no idea what to do. I sat in stunned silence looking at the list of problems until the end of class.

The bell rang. Remedial math was over. I stumbled out of that room in a fog. My ambition to prove I didn’t belong there had been completely crushed. I’d failed to complete so much as one problem. None of the other students talked to me as we shuffled back to class.

I’m not sure how long it went on like that. The only thing I remember was that I started to believe that maybe I did belong in remedial math. Why wasn’t it easy for me? Wasn’t this a class that was designed to help struggling students? Why was I completely lost?

The weird thing is that I have absolutely no memory of any of the classes after the first one. I told you I have a very good memory. I don’t understand why I can’t remember.

I wonder what happened.

I tried to do well on my regular assignments, but that didn’t help either. There seemed to be no way out of remedial math. I moved on from hopelessness to despair.

The breaking point came when the teacher announced we were about to watch a film. It was a stupid film about how to behave in school, but a film was always better than doing work. I put my pencil with the triangle attachment in my pencil case and leaned back. The lights dimmed and I felt a flicker of satisfaction about my imminent chance to relax.

Then the dreaded PA system again sprung to life.

“The following students are to report to remedial math…”

There would be no film on how to behave in school for me. I bit my lip, gathered up my things, and headed down to the boiler room.

That evening, I decided to give up my self-inflicted torment and beg my mother for help. I explained how I’d deliberately failed the placement test and how, no matter what I did, the teachers wouldn’t recognize that I was good at math.

My mom got on the phone and handled it.

“Why is my son in remedial math?”

“Well, he got a zero on the placement test.”

“Yes, but I’m looking at his grade from last year and he had a 97 percent.”

“Well, some students regress over the summer.”

“How’s he doing on his current coursework?”

“Let me look… hmmm, he seems to be getting all perfect scores. That’s strange.”

“This isn’t something that you noticed?”

After that phone call, I was no longer required to go to remedial math, but I remained shaken. I’m shaken now.

In high school I was one of the kids they sent to math competitions. Every time I went, I always thought about my failure in remedial math.

I graduated from college Summa Cum Laude with a degree in English and a minor in Physics. All I can think about when I look at that diploma is that I couldn’t get out of remedial math.

Remedial math taught me absolutely nothing about math, but it did teach me a very important lesson. I learned that once the dominant culture has decided that you’re not any good, nothing you do will ever make them change their minds.

Nothing.

They’ve judged you, they’ve found you lacking, and there’s no way to recover from that.

I was a good student from that day on, but no matter how well I did, there was always the lingering fear that they’d pounce on any excuse to find fault not just with my work, but with my essential self.

My second chance had come from external intervention, not from anything I’d done. You can’t “lift yourself by your own bootstraps” out remedial math.

I’d learned that once they had you down, they’d do everything in their power to keep you down. They taught me that with such ruthlessness at such a vulnerable age that there’s nothing anybody can say to make me think otherwise. I’ll take that lesson to the grave.

But in third grade I also resolved to oppose that systemic cruelty with every fiber of my being and every ounce of my strength until my last breath.

This is not the way you treat people. We should be helping each other up, not fighting to hold them down. Helping takes less energy and everybody wins.

Put those figures in a column and multiply them. It doesn’t take a math genius to recognize the answer.

___________________________________________________________________________

Thanks for reading everyone! As always, leave your questions or comments below!

I'd Rather Be Writing is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

My CoSchedule referral link

Here’s my referral link to my preferred headline analyzer tool. If you sign up through this, it’s another way to support this newsletter (thank you).

Oh geez, this sounds so much like Haiku School and Maui High, where I was relentlessly bullied by kids for being too smart (and a haole, of course) and by teachers for not being smart enough. I beat feet off that island as soon as I had my diploma from Maui High and haven’t been back. I am sure my 5th grade teacher, Mrs Range (my younger brother referred to her as Mrs Rage) would be shocked that I went on to graduate from university with a BFA and law school with a JD summa cum laude. She thought I was an undisciplined, indulged haole kid and despised and hated me. I was terrified of her - and when adults bully children, it is damaging. I have spent time in therapy figuring it out.

Thanks for this post! It reminded me of my education. I wasn’t in a small town; I was sent to Catholic school. From the very earliest I can remember, I had major trouble fitting in. I didn’t go to kindergarten, so when I got to 1st grade, I didn’t have any idea what to expect, but all the other kids were on top of it.

One day during the first week, the nun asked the class if they were ready to play music, so everyone but me stood up and went to a long cabinet under the windows, and grabbed pots and pans and wooden spoons and started to march around the room. I was already playing piano for about a year or so, and my mom was a church organist, so i just sat there horrified.

The nun asked me why I wasn’t playing music, and I said, “That isn’t playing music!” She got so mad at me that she made me sit in the coat room for the rest of the day! This was just the beginning, and it took me a while to realize that I had accidentally discovered sarcasm. Once I realized that, I started purposely using it to make myself feel better.

Your pencil story reminded me that when they were teaching me to write, I wanted to write with my left hand, but they told me not to, and made me write with my right hand instead. As a result, even a pharmacist can’t read my handwriting!

It all came to a head one day in High School. In religion class I asked why we had to eat fish every Friday, and then response was, “Because the Apostles were fishermen and we honor them.” I said, “It’s a good thing they weren’t fertilizer salesmen!” Of course I got suspended, and the only reason I didn’t get kicked out altogether was that my mom was connected by being an organist.

Throughout my whole experience in the Catholic school system, the main value was that I learned to be very skeptical about ideas and teachings. Every time I questioned anything, like the ridiculous Baltimore Catechism we were made to read, I saw that it infuriated the teachers, and realized that if your beliefs can’t stand up to criticism, you should question them to see why! The other thing I got was the ability to estimate small lengths with my hands, after having them whacked by rulers for 6+ years!