What Rural Folk Don't Know About the Lie They Call a Life

And how much that ignorance costs them

Note: It costs $25 to buy a new paperback, but you can support this newsletter for as little as $20 per year. Thank you so much, you make this possible!

I grew up in a town of 2,000 people. We lived out on the fringes deep in the wilderness. I still remember the feeling of dread that came over me when dad navigated the family vehicle down the crumbling asphalt roads that led to civilization.

The moment we set foot in town, the residents made it clear we weren’t welcome. Even business owners looked at us like they preferred that we’d just leave.

We went to the public school. It was as if the town thought the “real” kids went to the Catholic school. We were the “other” kids. We were the ones they could stick with needles.

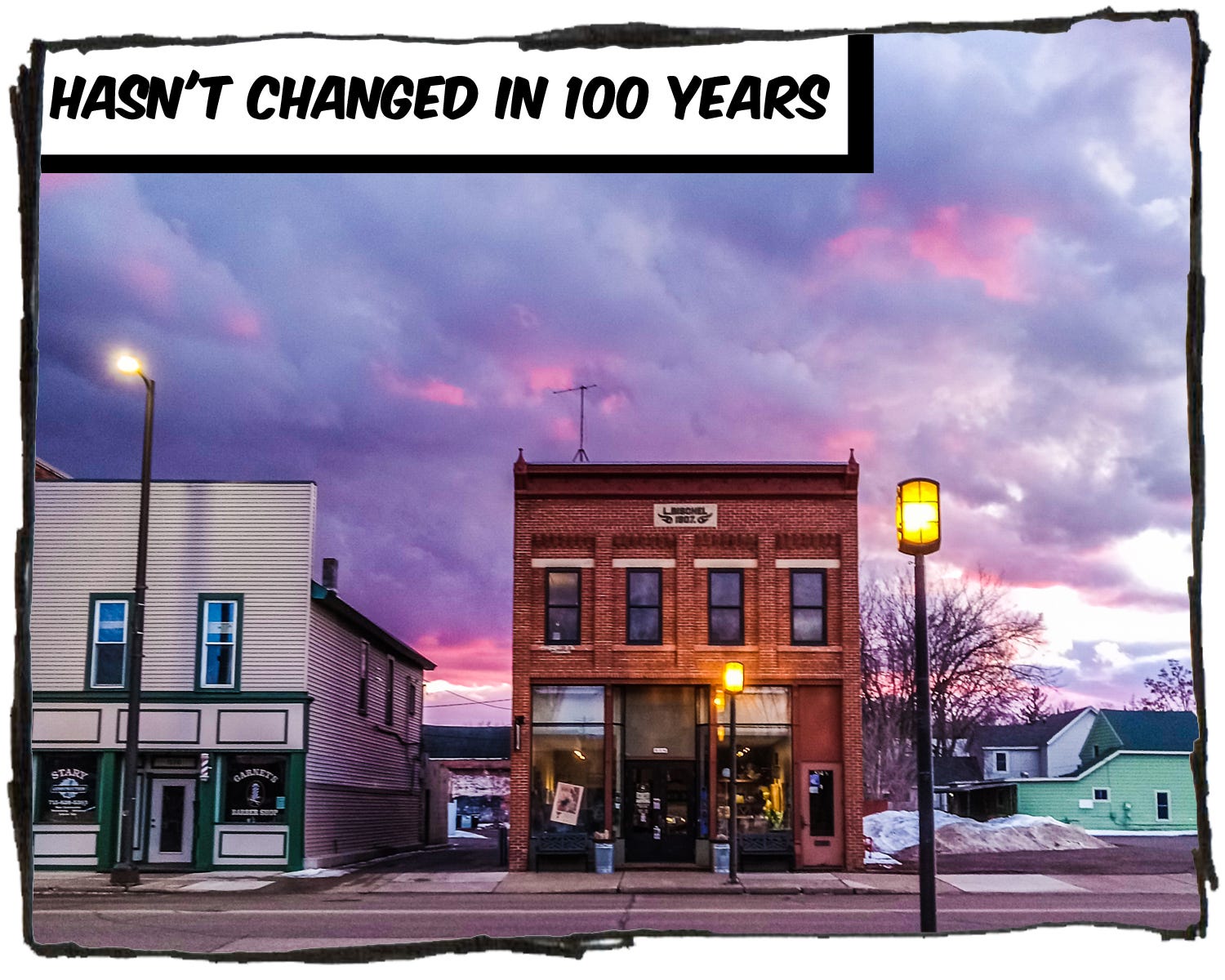

In a town that small, a couple people can have a big influence. You see their names plastered all over Main Street. They own the hardware store and the car dealership and the furniture store.

They win the elections.

They make the laws.

They own the town.

If you peered into the fish bowl from the perspective of the big city, it might seem harmless and ridiculous. You’ve got some delusional individual stomping around with cowboy boots and a Stetson hat thinking he’s the stud of the ranch.

It’s laughable, like a toddler playing sheriff.

But it’s not funny when you’re a small and vulnerable fish in that same bowl. All that preening and threatening is real. It’s very real.

The kids from the Catholic school received respect. You couldn’t clip them with your pickup as you made a sharp turn. The “burnouts” knew they had to jump out of the way.

I suppose the local farmers thought of the public school as a charity case. They didn’t say these things, but you could feel it. Even as a grade school child, you felt hate before you knew what hate was.

The men turned to watch you slowly as their cars rumbled by. They’d push you out of line if you were waiting to make a purchase. They’d yell at you for nothing at all.

“Get out of here you varmint.”

I can’t remember a single act of kindness from a stranger within the limits of that town.

To this day, I can see the neighborhood in my memories. They had doors you’d never think to knock on, not even on Halloween. Kids know where to go and when to run away. I’m glad I don’t know the horrors that took place behind the walls of those dilapidated houses.

Houses sitting in shadow. We drove by and the hairs stood up on the back of my neck.

The place called itself a town.

For twenty years that was the only life I knew. I both hated it and couldn’t escape.

What can you possibly think when you’ve put some distance between yourself and a place like that? You might come for a visit and people who used to treat you with absolute contempt are no longer capable of meeting your eye.

There’s never any accountability, only denial.

They don’t recognize you for what you were. The new version of you makes them afraid.

They fear anyone who knows how to navigate a city. They don’t go to those places. They hyperventilate when a highway splits into more than two lanes.

They clutch the wheel, knuckles white, “What do I do?”

They don’t remember the child you used to be, or what they did to you.

A town of 2,000 people is astonishingly quiet. You’d know this if you’d ever been a kid in a place like that. It’s natural for kids to ride around on dirt bikes and meet each other and laugh and howl and play.

Small town folk don’t like that noise. They’ll scowl at you when you’re young. They’ll call the cops when you’re a teen. They’ll watch you getting felt up by the pervert deputy and laugh from behind a smeary window.

There are ripples in the glass because the house is old. The house is falling apart. It could more appropriately be called a fishing shack than a home. The walls have soaked up a hundred years of misery and false promises. The old man inside has nothing to bring him joy but watching the torment of the young.

My heart rate elevates even as I think of this. We didn’t have the internet. We had movies. We had television. We had books.

I stockpiled books. I still stockpile them. I’m a hoarder when it comes to the written word.

If not for the books, I would have had no mentors.

We were farmers, but my dad acted as if the dynamic of the town didn’t apply to us. He farmed, but both he and his brother went to law school. I don’t know how that happened. I stopped talking to my father before I heard the story.

Farmers are good at finding government programs. With the way they denounce “socialism” you’d think that wasn’t true. But they’re better at it than anyone.

I understand that my grandfather was a farmer, but he died before I remember him. I do remember one thing. I remember a sense that an imposing power had gone. Everyone pretended to grieve, but when a rural patriarch gets put in the ground there’s a sense of relief.

There were a few buildings with his name on the side. He was one of those.

Grandma was a teacher.

My dad practiced for a time in our mud hole of a community. He quit when he realized he made more farming.

But small town folk remember, and they’re afraid of lawyers. Dad would saunter in and act as if his name was up there next to the others on Main Street.

The Main Street men were bullies. Like all bullies, all you have to do is call their bluff. Why tangle with the uncertainty of my dad when there were weaker people who made easier victims?

Like the kids riding around on dirt bikes.

Like me.

See how fast they can go.

See if they can outrun a truck.

I learned a lesson from my father, one that he probably didn’t intend to teach. One day when the jerk in his cowboy boots and his cowboy hat beckoned to me as if I had been put on this Earth to obey, I gave him the finger, but I didn’t run away.

You can watch one of those big fish in a small town go through the four stages of realization. They’re pretty entitled, and small town folk are never in a rush, so it takes about as long as it does a tube television to warm up enough to create a picture.

First their eyes flash in anger. Then they open their mouths to threaten you. Sometimes they manage to howl a threat.

You must not back down. All is lost if you back down.

You have to look them in the eye, and call them the worst thing you can imagine. You have to mean it. You can’t show fear. With every fiber of your being, you have to believe that you’re better than they are. You have to believe they’re nothing. You have to allow that conviction to radiate out of you like heat off the sun.

“Do you know who I am? You better shut your mouth and get back in that rusty truck and get out of here or my dad will hear about it.”

And if you say that, those false big fish turn around and skitter away like a minnow. Because deep down they know they’re nothing. They cast a spell on everyone else within city limits, and they’re content to go and find an easier victim when they’re challenged.

The sad thing is, this is the dynamic that runs our whole world. Most people never get so fed up with terror that they decide to go down swinging. They’re afraid of the consequences, but they never consider the consequences of not putting up a fight.

You’ve got to have that moment where you stand fast and say, “To hell with it, I’d rather die that put up with this.” It only works if you’re actually willing to die.

The conflict evaporates like a soap bubble.

The people of rural towns don’t see anything wrong with the lie they call a life. Perhaps it’s because the big city folk aren’t inclined to pop the bubble of overreaching bullies.

Maybe it’s time to start.

“I'd rather Be Writing” exists because of your generous support. If you have the means please consider upgrading to a paid sponsorship. I have payment tiers starting at as little as twenty dollars a year. I'm so happy you're here, and I'm looking forward to sharing more thoughts with you tomorrow.

My CoSchedule referral link

Here’s my referral link to my preferred headline analyzer tool. If you sign up through this, it’s another way to support this newsletter (thank you).

Utter bullshit. I'm 67, live in the midwest, grew up and worked in small towns most of my life. This is fiction. Nothing remotely close to reality.

I grew up on a dairy farm, 3 mi from the closest neighbor farm which belonged to my grandpa, and 15 mi from town. Which had a population of 1,200 souls and 6 churches. HS graduation class of 48 kids total. By 14 I could run all the equipment for a 1,000 acre farm, and milk 130 head, without any adult supervision. As well as drink beer and hunt, not in that order. At the time I hated back-breaking work, 7 days a week, regardless of -30 F or 95 F, starting every morning at 5 am. Were you sick? Cows need milking. Tired? Cows need milking. Break your arm? Cows need milking. But with all that, I have no idea what Walter Rhein was writing about. 40 years later, after years of living and working OCONUS and traveling to 99 different countries, I’m back living on a farm, dirt road and 1 mi driveway to boot. My neighbors with 4 legs outnumber to 2 legs by 100 to one. And I love it. I have no idea where Walter grew up but it’s unlike any rural part of the US I’ve been to.